52% of enterprise employees report that they have less than 30 minutes a week for structured learning, according to internal L&D benchmarking data that circulates quietly across large organizations. Numbers like this surface often in large environments, largely because they align with what teams already see.

Anyone who has spent time inside day-to-day operations recognizes the pattern- learning time is rarely planned. It is picked up where it can be found, between meetings, after system updates, or during short pauses that were never intended for instruction. Formal courses still exist, but they now sit alongside expanding queues of operational work. Over time, the outcome becomes familiar. Longer programs are pushed out, shorter ones are sampled, and completion rates lose relevance.

Against that backdrop, this blog focuses on how learning adapts when time is fragmented, systems are layered, and performance expectations continue without pausing for training windows.

How Time Replaced Motivation in Workplace Learning Decisions

Most enterprise learning breakdowns are still explained as engagement problems. Employees are labeled as disengaged, managers as inconsistent in reinforcement, and content as misaligned. These explanations persist largely because they are familiar, not because they accurately describe how learning fails inside real work environments.

When learning remains optional, but work does not, time becomes the deciding variable, a dynamic that has long shaped how corporate training competes with day-to-day execution. Motivation rarely disappears in these settings. It gets pushed aside by inbox volume, system alerts, approval steps, and deadlines that arrive with consequences attached.

Training competes with those pressures and usually loses, which is why even well-regarded programs are postponed and, over time, quietly abandoned. Under sustained time pressure, predictable patterns emerge. Employees begin modules with the intention of returning to them later, assuming space will open up, but it rarely does.

Sessions are paused partway through and left unresolved, while knowledge checks are completed primarily because answers are easy to infer in the moment. The system records completion as expected, yet the underlying capability does not meaningfully change.

This distinction shapes the response. When learning failure is framed as a motivation issue, organizations invest in better content or stronger messaging. When it is treated as a time constraint, attention shifts toward design decisions that govern how learning fits alongside work.

Duration > Placement > Access.

This is typically where MITR Learning and Media enters early conversations, not by redesigning content first, but by mapping how learning competes with operational demands across specific roles and functions.

Once time is acknowledged as the constraint of shaping other decisions, attention turns to what actually holds when learning is compressed.

Why Microlearning Alone Does Not Improve Retention at Work

Once time is treated as the primary constraint, learning design often shifts toward shorter formats, continuing a broader pattern seen across corporate training over the past decade. In enterprise environments, that expectation is unreliable. Short content lowers the barrier to entry, but it does not change how memory behaves after exposure.

Over time, retention erodes for familiar reasons:

- Learning is encountered once, without planned return points

- Content is completed outside the moment it is needed

- Recall is tested immediately, not over time

- Reinforcement is optional rather than designed

- Application depends on individual initiative

- Measurement favors completion over use

When these conditions exist, just-in-time learning tends to function as a passive reference layer. Employees may recognize its relevance, but under pressure they default to familiar workflows rather than searching for guidance that feels slightly removed from the task.

MITR typically addresses this gap by treating just-in-time learning as a system-level behavior rather than a content attribute, aligning learning triggers with workflow signals, role-specific actions, and system events that already govern how work progresses.

As timing becomes more precise, the limits of disconnected systems become harder to ignore, bringing workflow integration into sharper focus.

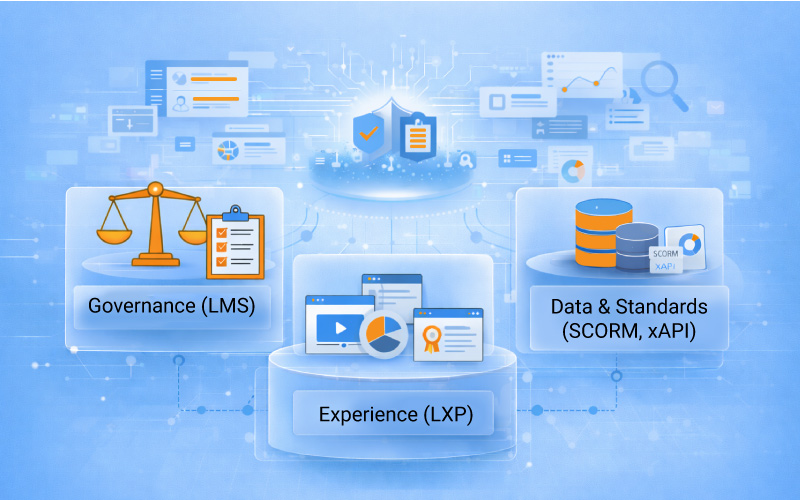

Why Learning in the Flow of Work Depends on System Integration

- Right Timing Is Not Enough: Learning can surface at the correct moment and still fail if it sits outside the systems where work is executed. While better timing improves access, it does little to reduce the friction created by switching tools in the middle of a task.

- Learning Tools Often Sit Beside Work, Not Inside It: In many enterprises, employees are expected to pause their task, move to a separate learning environment, and then return to complete the work. This sequence may appear manageable in theory, but under pressure, those transitions are skipped, and learning becomes optional by default.

- Context Is Lost When Systems Are Disconnected: Learning platforms that lack visibility into task state, live data, or workflow progress deliver guidance that feels generic. Even relevant content loses impact when it arrives without a situational context.

- System Design Shapes Learning Behavior: Learning in the flow of work depends less on content quality and more on how tightly learning assets connect with operational tools, decision paths, and data sources. Integration determines whether learning feels adjacent or embedded.

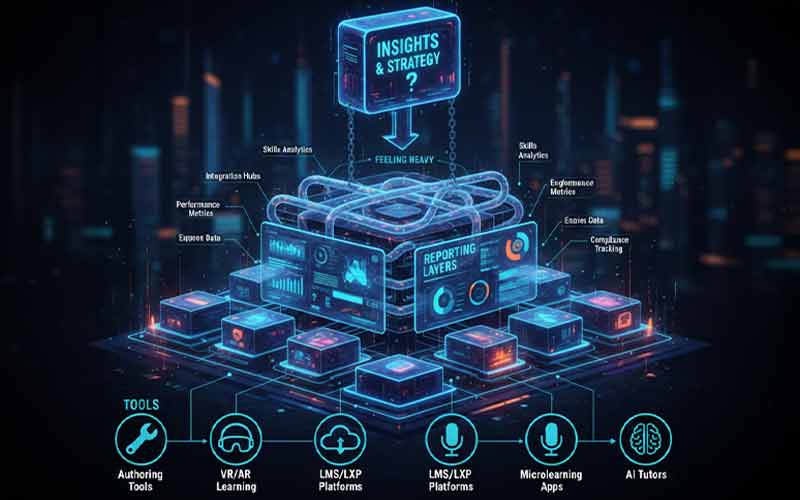

- Integration Changes What Can Be Measured: As learning becomes embedded in work systems, visibility into usage improves, but evaluating impact requires moving beyond basic activity data.

As integration deepens, the overlap between learning activity and work activity becomes harder to separate, which shifts attention toward how microlearning effectiveness is measured.

How Microlearning Effectiveness Is Measured Beyond Completion Data

As microlearning becomes more embedded in daily workflows, measurement becomes less straightforward. Indicators such as clicks, completions, and time spent are still easy to capture, but on their own, they say little about whether learning is influencing behavior or improving performance.

In enterprise environments, this gap shows up quickly. Microlearning often generates high levels of visible activity with limited interpretive value. Short modules are completed quickly, sometimes more than once, which inflates engagement metrics without clarifying how learning is used once work resumes. Measurement appears positive, while operational patterns remain largely unchanged.

Over time, more useful evaluation tends to rely on indicators that extend beyond platform activity:

- Access at decision points, showing whether learning appears when choices are made

- Repeat usage over time, suggesting reinforcement rather than single exposure

- Workflow correlation, where learning activity aligns with task execution

- Delayed performance signals, observed after learning has had time to influence outcomes

This approach requires connecting learning data with operational data rather than reviewing learning metrics in isolation. Without that connection, microlearning remains easy to track but difficult to evaluate in practical terms.

As measurement practices mature, attention shifts toward sustainability, particularly how microlearning performs as programs expand across roles, teams, and regions.

How Microlearning Performs When Deployed at Enterprise Scale

As microlearning expands beyond pilot groups, its limitations become more visible. What works for a single team does not always translate cleanly across roles, regions, and operating models. Scale introduces governance and consistency challenges that are often underestimated early on.

At the enterprise level, content volume grows quickly while ownership becomes fragmented. Similar topics emerge in parallel, framed slightly differently, which dilutes clarity and relevance over time. Usage patterns become uneven, not because demand disappears, but because trust in accuracy erodes.

Sustainability depends on disciplined lifecycle management. Short learning assets require regular review and alignment with changing processes. When updates lag behind operational change, even well-designed microlearning loses credibility and is bypassed in practice.

At this stage, microlearning functions less as a content tactic and more as an operating model shaped by governance and upkeep.

Microlearning delivers value when it reflects how work actually unfolds, fragmented, system-led, and shaped by immediate decisions rather than training schedules. MITR Learning and Media supports enterprise learning by aligning microlearning with workflows instead of forcing it into fixed structures.

For teams reassessing how learning operates in practice, reach out to MITR to begin that conversation.

FAQ's

1. How can K–12 teachers boost student engagement in digital learning?

Teachers boost engagement by adding quizzes, polls, and small group activities. They encourage students to work together, share ideas, and give feedback right away. This keeps students interested and helps them really understand the concepts.

2. What strategies make online learning effective for K–12 schools?

The most effective online learning keeps lessons short and clear. Teachers give students hands-on exercises and guide them as they work. Students test ideas, think about what they do, and move at their own pace.

3. How can schools design age-appropriate digital content for students?

Schools should create K-12 digital learning content that matches each age group. Younger students enjoy visuals, animations, and simple interactive activities. Older students do better with projects, real-world problems, and group discussions.

4. Which edtech tools work best for personalized learning in K-12 classrooms?

The best edtech tools for K-12 digital learning let each student learn at their own pace. Teachers quickly spot which students need extra support. When students collaborate and share ideas in digital learning activities, lessons become more engaging, and students learn better from each other.

5. What are the common mistakes to avoid in K-12 digital learning?

Common mistakes include long videos without interaction and one-size-fits-all platforms. Giving too much content at once or providing little teacher guidance can overwhelm students. Ignoring accessibility needs also makes learning harder. These issues reduce engagement and overall learning effectiveness.