In enterprise learning systems, accessibility often enters through compliance requirements rather than learning design.

Over the last two years, accessibility checks have started appearing later in learning projects, sometimes at pilot review, sometimes during procurement, and occasionally after launching when a problem is flagged that should have been visible much earlier.

The timing matters because it reflects how accessibility is positioned inside enterprise learning systems. In many organizations, accessibility is reviewed by teams outside learning design, typically legal, risk, or procurement, and assessed against a standard rather than learner experience.

Policy updates, RFP clauses, and external audits drive action more often than learner feedback, particularly in the US and parts of Europe where digital accessibility in education is no longer optional.

The result is a narrow definition of accessible learning, shaped by compliance logic instead of design intent, and that framing sets the boundaries for everything that follows.

Why Accessibility Entered Learning Through Compliance

In most organizations, accessibility entered enterprise learning through legal, procurement, and risk channels rather than through learning strategy or learner experience design.

In most enterprise environments, accessibility did not emerge from learning strategy discussions. It surfaced through regulation, procurement requirements, and legal interpretation. ADA-related risk in the US, WCAG alignment for global rollouts, and European accessibility directives pushed the issue into view, often through channels that sit adjacent to learning rather than inside it.

That origin matters- because compliance teams are trained to look for evidence, including checklists, artifacts, and statements of conformance. Their job is not to evaluate how a learner with low vision navigates a branching scenario or how an older employee processes dense on-screen text after a long shift. Their job is to reduce exposure, and learning teams often inherit that framing even when they do not intend to.

A few patterns show up repeatedly.

First, accessibility is treated as a review of milestones rather than a design constraint. Content is built; interactions are approved, and only then does accessibility enter the conversation. At that point, remediation focuses on what can be adjusted without reopening core design decisions. Color contrast can be corrected. Alt text can be added relatively late, but navigation logic, pacing, and modality choices are much harder to revisit once decisions are locked in.

Second, standards become proxies for learner experience. WCAG criteria and ADA guidance are necessary, but they are often interpreted narrowly as conditions that are either met or unmet. Teams focus on satisfying the requirement rather than examining how it maps to actual use. Compliance is achieved, while usability remains uneven.

Third, responsibility becomes diffused. Accessibility belongs to everyone and no one. Learning designers assume standards will be handled elsewhere; vendors wait for direction, and internal reviewers focus on documentation, creating motion without clear ownership.

This compliance-led entry point explains why accessible learning is frequently discussed as a constraint instead of as a design discipline. It also explains why learner diversity is often addressed superficially. Once accessibility is framed as something to be satisfied, not designed for, the range of learner needs that are considered relevant narrows quickly.

That narrowing shows up most clearly when teams start talking about who accessibility is for. At that point, assumptions about the “typical learner” surface, and many forms of variation are quietly excluded. That is where the next issue begins.

How Learner Variability Gets Reduced to a Few Assumptions

When accessibility is handled through compliance, learner variability is reduced to a narrow set of assumptions about who learning systems are designed for.

Enterprise learning environments tend to operate with an implicit model of the learner. It is rarely written down, but it is consistently reinforced through design choices. Typically, that learner is assumed to be mid-career, digitally fluent, working on a standard device, and able to engage with content in uninterrupted blocks of time. Course length, interaction density, assessment timing, and platform behavior all reflect this model, even when teams believe they are designing for broad audiences.

Under that framing, the model remains largely intact. Adjustments are made around it rather than against it. Learners with permanent disabilities are acknowledged, usually in narrowly defined ways, while other forms of variation are treated as secondary or situational rather than structural.

A few patterns tend to appear.

-

Age-related differences surface as workforces skew older across many industries. Visual processing speed, short-term memory, and tolerance for dense interfaces change over time. These shifts do not register as disabilities in most systems, but they influence how quickly learners move through content and how much cognitive load they can manage at once.

-

Temporary impairments are common but rarely planned for. Fatigue, injury, medication effects, or environmental constraints all shape how learners interact with digital learning. Design decisions that assume consistent attention, precise motor control, or uninterrupted audio access quietly exclude these learners without triggering formal accessibility concerns.

-

Language and processing differences often sit outside standard compliance discussions. Learners working in a second language, or those who process written information more slowly, struggle with tightly paced modules or information-heavy screens. WCAG criteria may be met, while comprehension and completion rates decline.

What connects these forms of variability is that they do not map cleanly to compliance categories, which makes them difficult to audit, harder to document, and therefore more likely to be handled informally, if they are addressed at all, through facilitator support or learner self-adjustment.

Once these assumptions are embedded, design decisions begin to compound, with content density increasing, interaction patterns growing more complex, and flexibility reduced in the name of efficiency. Accessibility remains technically present, but inclusivity narrows in practice.

Why Inclusive Learning Design Is Structural Work

Inclusive learning design is shaped long before accessibility reviews begin. It sits in early decisions that determine how much variation a learning system can absorb once it is live. These decisions are not always visible, but they set limits that remediation cannot easily cross.

Some of these limits are introduced quietly.

-

How content is chunked, and whether learners can control the sequence

-

Whether interaction patterns stay consistent or shift from screen to screen

-

How tightly time, progress, or completion are enforced

Other constraints come from infrastructure rather than pedagogy.

-

Platform choices that restrict layout flexibility

-

Authoring tools that hard-code interaction behavior

-

Templates optimized for speed, not variation

None of these decisions signals exclusion on their own. Together, they narrow the range of learners who can move through experience without friction.

This is where intent and outcome begin to diverge, because structures built around a narrow set of conditions make inclusion dependent rather than inherent. Learners adjust by slowing down, skipping steps, or disengaging altogether, while the system itself remains unchanged.

Over time, accessibility work gravitates toward what can be adjusted without reopening these structural choices. Inclusive design, which requires revisiting assumptions about pacing, control, and format, is deferred because it is harder to isolate and harder to justify lateness.

That difference becomes more visible once standards re-enter the conversation, not as abstract guidance, but as rules applied to systems already in motion.

How WCAG and ADA Function in Practice

In enterprise learning environments, WCAG and ADA tend to be applied as post-hoc evaluation standards rather than as inputs into early learning design decisions.

They are often described as design guidance, but in practice they are applied after learning assets are already in place. WCAG compliance is frequently assessed as a set of conditions to be verified rather than as a signal of whether the system was designed to absorb variation from the start.

This changes how teams engage with the standards.

-

Criteria are interpreted narrowly, usually as pass or fail checks tied to visible elements.

-

Evidence becomes the focus- screenshots, conformance statements, remediation logs, and anything that can be produced during review.

-

Areas that are harder to verify receive less attention.

-

Ambiguity is avoided, even when the learner experience sits inside it.

Teams often optimize what can be validated, which allows courses to meet technical requirements while still placing sustained demands on attention, reading speed, or interaction timing that many learners cannot maintain.

When standards are applied late, they inherit existing design limits, correcting surface issues while leaving pacing and modality decisions unchanged, so accessibility is documented, but flexibility remains limited.

In global learning environments, WCAG and ADA compliance support consistency and risk management, particularly in organizations aiming to demonstrate ADA compliant learning in the US, but they do not reflect how learners engage across age groups, language contexts, or working conditions, shifting responsibility toward documentation rather than toward earlier design decisions.

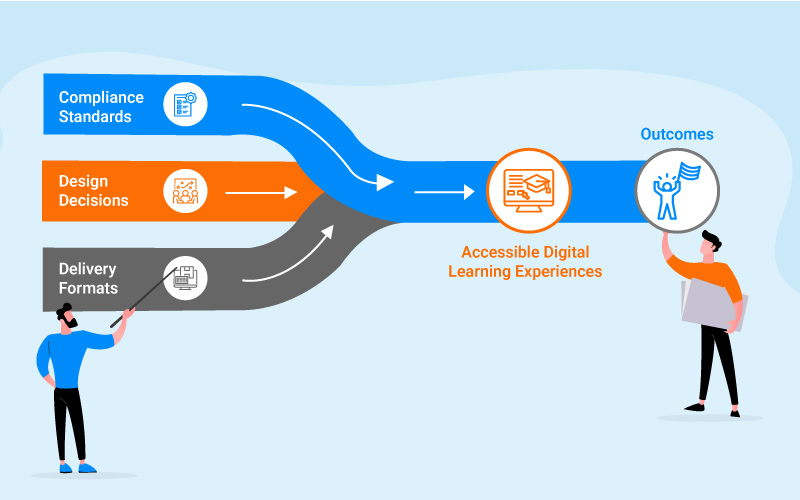

How Learning Formats Shape Accessibility in Practice

Learning formats shape accessibility in practice because they determine how much control, effort, and cognitive endurance learners need over time.

Delivery is where earlier design and compliance decisions become visible in use. Once learning moves into real workflows, formats determine how much control learners have, how fatigue accumulates, and how much variation the system can absorb without support. Accessibility may be present at a technical level, but formats shape whether that access translates into steady progress or repeated friction.

-

Video-heavy formats rely on captions and transcripts for compliance, but long runtimes and linear pacing still assume sustained attention and uninterrupted time, which many learners do not have.

-

Text-dense modules increase reading and processing load, particularly for learners working in a second language or returning to structured learning after long gaps, even when navigation technically meets standards.

-

Highly interactive designs introduce timing pressure through branching paths, multi-step tasks, and fixed sequences, which can disadvantage learners who need more time or simpler interaction patterns.

-

Limited format mixing reduces recovery options, pushing learners to adapt their behavior instead of allowing the system to adapt to them.

Over time, the impact of these format choices becomes uneven, not because learners differ in motivation or capability, but because the same structures place different demands on people at different stages of their working lives.

Where Accessibility Becomes Uneven Over Time

The effects described earlier rarely appear as a single failure point. They surface gradually as learners spend more time inside the same systems and small frictions compound, particularly when design assumptions that once felt workable begin to strain under changing roles, time constraints, and cognitive demands.

Age is part of this picture, but it tends to show up through ordinary shifts rather than clearly labeled accommodations.

Visual fatigue increases, processing speed changes, and tolerance for dense interfaces or tightly timed interactions declines, especially when learning is delivered in rigid formats layered onto already demanding work. These changes are slow enough that they are often interpreted as disengagement or preference rather than as signals of design mismatch.

Work context matters as much as age. Senior roles often involve less uninterrupted time, greater reliance on selective learning, and more frequent interruptions, making fixed pacing and uniform pathways harder to sustain.

Systems can remain technically accessible while still placing uneven effort demands across the workforce, causing accessibility to vary in practice rather than hold steady by design.

At MITR Learning and Media, accessibility work in enterprise learning environments often begins when systems start to show strain, during compliance reviews, global rollouts, or attempts to modernize existing platforms. Attention is directed less toward isolated fixes and more toward the design assumptions that shape learner effort over time, including how learning is paced, how formats behave across modules, and how much flexibility is built into progression and navigation.

This focus positions accessibility as a property of learning system design rather than a feature added after the fact, allowing inclusion to hold more consistently as work contexts, learner profiles, and organizational demands evolve.

If these questions are already part of how learning design is being discussed within your team, this is often the right moment to connect with MITR Learning and Media.

FAQs

1. What is learning ecosystem transformation?

A learning ecosystem transformation is the redesign of how learning is created, delivered, connected, and measured across K12, Higher Ed, and Enterprise environments. It aligns media, data, and design to ensure learning becomes continuous, measurable, and future-ready.

2. Why is media essential in modern learning ecosystems?

Media improves attention, emotional engagement, and comprehension. Visual storytelling helps learners grasp complex ideas faster, whether in schools or enterprise settings. In MITR’s ecosystem, media plays a central role in making learning memorable and meaningful.

3. How does data improve the way we learn?

Data helps educators and organizations identify gaps, measure progress, personalize learning, and improve performance. MITR applies data-driven insights to ensure learning outcomes are not assumed, they’re understood.

4. How does design shape scalable learning ecosystems?

Design ensures learning experiences are structured, accessible, and outcome-focused. Clear sequencing, intentional flow, and cognitive principles make content easier to absorb and apply. MITR uses design as the backbone of every learning experience it builds.

5. What roles do upside learning, mynd, and BrinX.ai play?

Upside learning strengthens mitr’s ecosystem with science-backed instructional design, analytics, and enterprise capability frameworks.

mynd enhances enterprise learning through high-end media and storytelling, influencing how MITR approaches creative engagement.

Brinx.Ai accelerates content creation across segments, turning raw content into structured learning modules with AI precision.

6. How does MITR support both education and enterprise globally?

MITR works across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and the USA to unify learning principles and capability frameworks across schools, campuses, and organizations, all under one connected ecosystem philosophy.

Soft Skills Deserve a Smarter Solution

Soft skills training is more than simply information. It is about influencing how individuals think, feel, and act at work, with coworkers, clients, and leaders. That requires intention, nuance, and trust.